We hear a lot about strategy of late, or at least the alleged absence of one to guide our efforts against the Islamic State. The President says he wants to contain, degrade and eventually destroy ISIS and claims to have a strategy for achieving that goal. And in fact, he does. The administration's strategy is to help those in the region who are opposed to ISIS with training, equipment and air support. More recently those measures have been augmented with some special operations teams operating in direct support of the Kurdish Peshmerga. The real question then is not whether the administration has a strategy, but rather does the strategy they have chosen have a realistic chance of achieving the goal of containing, degrading and eventually destroying ISIS.

The chosen strategy seems to be based on several assumptions, two of which have been tested and found wanting. The first is that there exists in Syria an organized resistance composed of moderate Sunni Arabs that, with training and other assistance from the U.S. and its allies, could topple the Syrian dictatorship. That turns out to have been a bad assumption, though some assert we have just been too demanding in our search for potential allies. It is also assumed that the Iraqi government can be persuaded to respect the rights of its Sunni Arab and Kurdish minorities, and to distribute aid meant for those groups in accordance with our intent. That has not happened. Finally, it is assumed that the introduction of U.S. ground forces in significant numbers would be counterproductive. Any gains they might deliver would be temporary and likely come at a high cost. That assumption has yet to be tested. Some would say our experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan are sufficient validation. Others would cite the first Gulf War and argue that if committed to a well defined mission and withdrawn promptly upon completing the job, ISIS could be defeated at a cost our citizens would be willing to bear.

When key assumptions on which a strategy is based are proven false or called into serious question, it is time for a new strategy. But just what might such a strategy look like? And how should we go about developing one that might work? Strategies are the tissue that connects ends and means. The ends sought by the President are to contain, degrade and eventually destroy ISIS. The available means have been constrained to exclude any substantial number of U.S. ground forces, and limit air strikes to those with a near zero probability of inflicting civilian casualties. Under those constraints, the best any strategist is likely to do is propose a version of the current strategy that relies on fewer assumptions.

Option 1 - Minimal Relaxation of Political Constraints

Such a strategy might be centered around the Iraqi Kurds, their Peshmerga militia, and the Kurdish minority in Syria. Military training and materiel support would be provided directly, bypassing Baghdad in the case of the Iraqi Kurds, and at the maximum rate those forces prove able to absorb. A secondary effort would focus on the Sunni tribes in western Iraq and eastern Syria, again bypassing Baghdad. Special operations teams would be employed to persuade those tribes to join the fight to expel ISIS from Iraq and defeat them in Syria. Those found willing would be provided training and arms. Special operators would be committed at the maximum level deemed to be sustainable by the U.S. and those coalition members with those capabilities. Air support would be sufficiently robust to ensure that no request for reconnaissance or fires could not be met. the U.S. would establish a multinational theater operations center in northeast Iraq, not Baghdad, to help integrate operations throughout the theater and provide effective command and control.

There would be three major lines of effort; military, diplomatic and information. Diplomacy would be the main line of effort with both military and information operations in support. The middle east is an incredibly complex diplomatic challenge and will require a multi pronged diplomatic offensive. Turkey's Kurdish minority has been in conflict with the government in Ankara since Turkey emerged from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire. Many Kurds seek a degree of autonomy similar to that enjoyed by their cousins in Iraq. The Turkish government has shown no interest in that solution to their century old conflict with the Kurds. They focus instead on suppressing what has become a low level rebellion in their Kurdish provinces. That conflict threatens the success of any military campaign that relies on Kurdish forces. We need them to declare at least a temporary truce and will need some diplomatic magic to achieve that end.

The Iraqi government will not be pleased when we bypass them to work directly with their Kurdish and Sunni minorities. They are likely to view those efforts as a threat to their sovereignty and a retreat from our commitment to help rebuild Iraq's military. Unfortunately, they will be right on at least one of those counts. The strategy we suggest, if successful, would almost certainly lead to the division of Iraq into semi-autonomous Shia, Sunni and Kurdish zones. What's more, Iraq's Iranian sponsored Shia militia could sabotage our efforts to recruit Iraq's Sunni tribes if they chose to do so. It is hard to say which of our many diplomatic challenges is the most severe, but persuading the Iraqi government to acquiesce in our plan to work directly with their Kurdish and Sunni minorities, and to restrain their Shia militias, must rank near the top.

But clearly, the most difficult diplomatic challenge of all is found in Syria. It is a place where the interests of the U.S., its European allies, Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iraq and Jordan collide. All would like to see an end to the civil war that has turned Syria into a cauldron of violence. All would like to put an end to ISIS. But there are sharp differences over how post-war Syria should be ruled. If our military line of effort is to move beyond containing and degrading ISIS, we will need forces on the ground to finish the job. The Kurds have no interest in taking the fight that far and the Arab opposition in Syria is too feeble. The forces we need must come from within the region, but those who might provide them will not do so while Bashar al-Assad remains in power. That is the circle we must ask our diplomats to close.

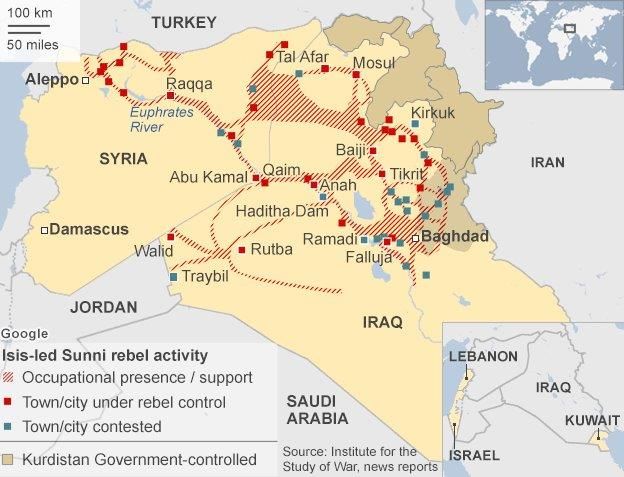

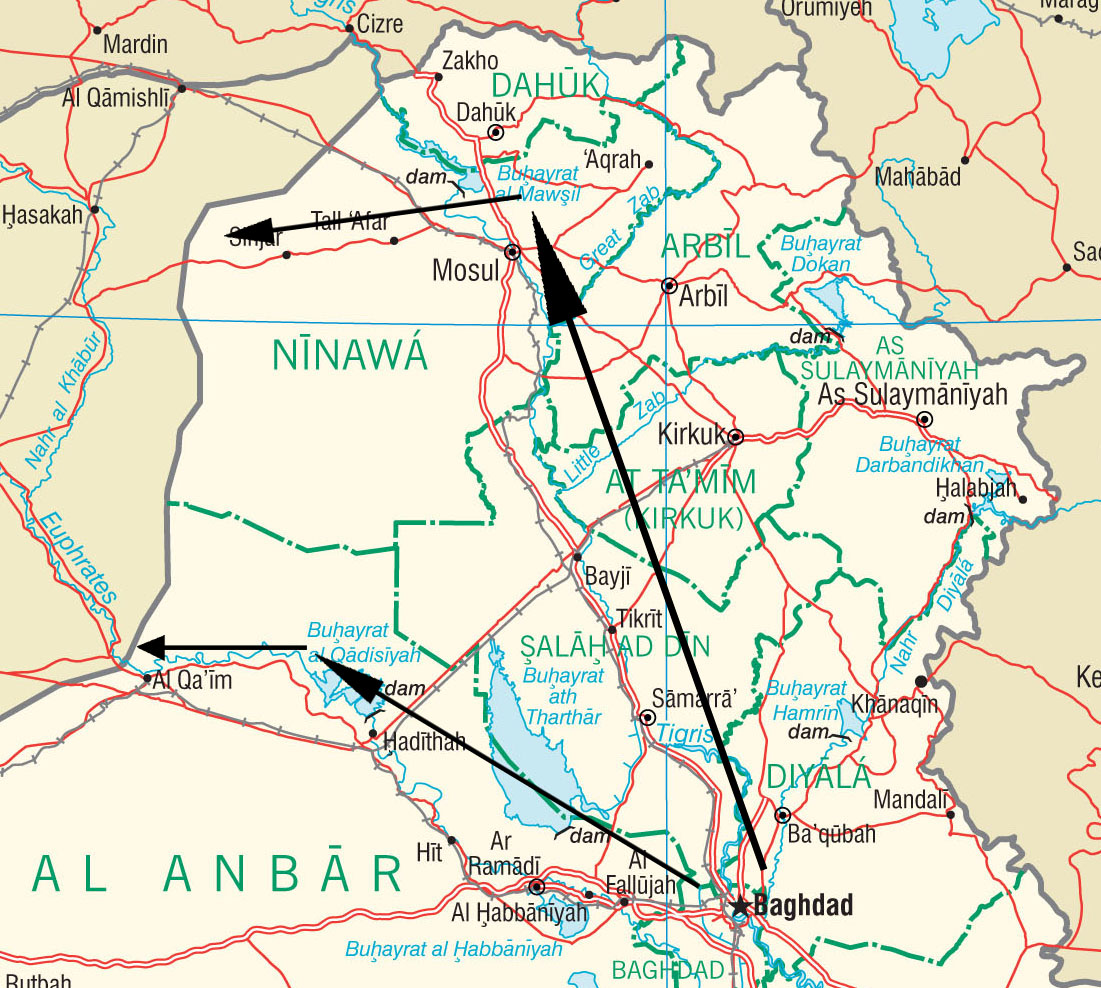

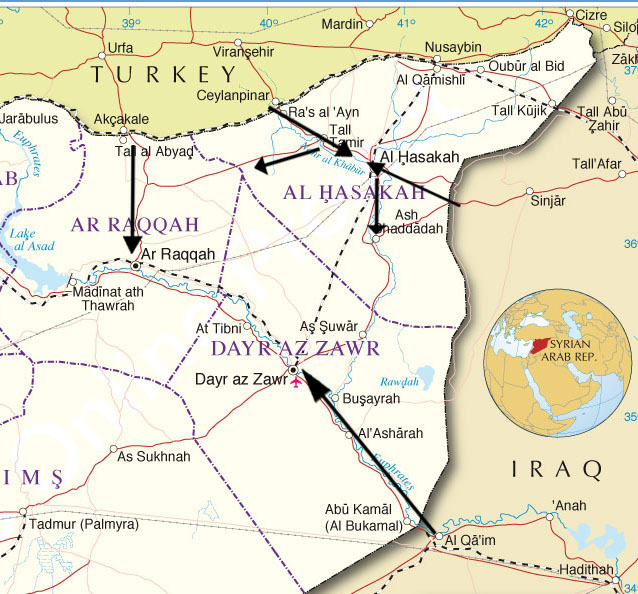

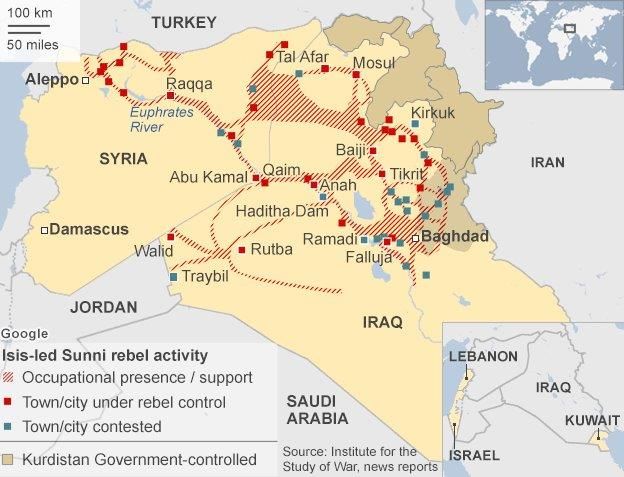

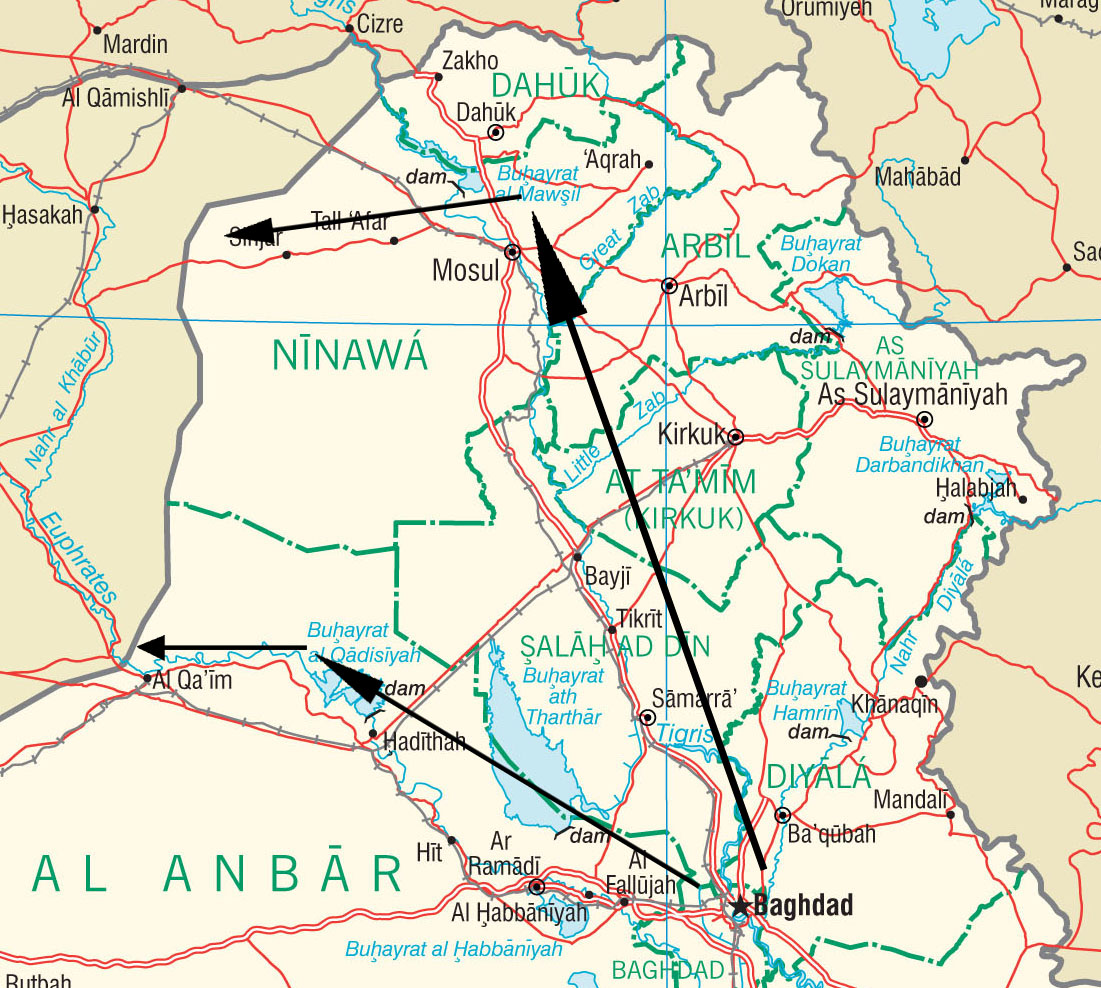

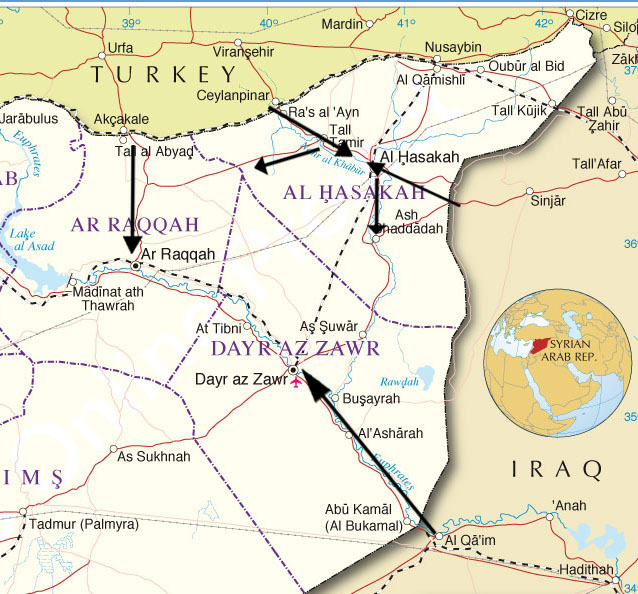

The initial military objective would be to gain control of Iraqi territory north and east of the highways linking Baghdad, Samarra, Tikrit, Baiji and Mosul; then west to Tal Afar, Sinjar and the border with Syria. That effort would fall largely to the Kurdish Peshmerga, with help from those Sunni Arab tribes that prove willing. In the south, the objective would be to reestablish moderate Sunni control over the major population centers of Fallujah, Ramadi, Hit, Haditha and Qa'im; as well as the highway connecting those cities. In Syria the early efforts would focus on helping the Kurds establish firm control over the area east of the highways linking Ra's al 'Ayn, Tall Tamr and Al Hasakah; and north of the highway between Al Hasakah and Rabiia on the border with Iraq. Airstrikes targeting ISIS would continue in both Iraq and Syria at a tempo limited only by our ability to find targets and the constraints on putting non-combatants at risk. Given the importance of the diplomatic line of effort, especially in Syria, we will establish a diplomatic liaison at our multinational theater operations center to help focus the direction and pace of military and information operations in ways that will contribute to the success of our diplomatic efforts.

Our third line of effort, information operations, will focus on disrupting and countering the ISIS campaign of recruitment on social media. The major theme will be to paint ISIS as a bunch of losers who have attempted to hijack the Muslim faith and are blaspheming Allah and corrupting the revelations of Muhammad. Since the messenger is as important as the message we will recruit Muslim faith leaders who are opposed to political Islam to make this case for us. As we flood both conventional media and social media with our message, capitalizing on every diplomatic and battlefield success, we will also use every technical means at our disposal to deny ISIS access to the internet or corrupt their message when they gain such access. If additional legal authorities are needed to make these efforts effective, we will seek them.

The strategy proposed here might lead to the destruction of ISIS, but the odds of success are not as high as we would like. A bit more tolerance for collateral damage from airstrikes would improve our odds, but the dependence on some sort of diplomatic breakthrough in Syria suggests a need for an option that would be less dependent on diplomatic magic. Some modest relief on the constraints regarding the use of U.S. ground combat forces would open the way to such an option. It would not take a lot. Two Stryker Brigade Combat Teams would substantially improve our odds of success.

Option 2 - Modest Relaxation of Political Constraints

If made available by the President, we would propose using those two brigades as a mobile reserve during initial operations in Iraq. They would not be asked to take and hold terrain. That would be the task of our Kurdish and Sunni Arab partners. But those brigades would bring mobility and firepower that those partners do not have. We would propose that they be postured to respond quickly to turn the tide of battle when ISIS threatens to prevail or exploit success when they are defeated. Such a force, perhaps 10,000 soldiers, would improve the ability of our special operations teams to recruit Sunni tribes to our cause and dramatically hasten the eviction of ISIS from Iraq.

At the conclusion of combat operations in Iraq our Kurdish and Sunni Arab partners would be fully committed to governing the areas seized from ISIS control. The Stryker Brigades would be deployed in western Iraq, poised to enter the fight in Syria when our diplomatic efforts are deemed to have failed or when their movement might be seen as the stimulus needed to move diplomacy forward. Their very presence might be enough to bring the so-called moderate opposition in Syria into our orbit. Even better, their presence might be enough to persuade Syria's Arab neighbors and/or Turkey to contribute ground forces. Should that happy circumstance present itself, we would be in position to replicate our success in Iraq. With local forces in the lead and our Stryker Brigades acting as a mobile reserve, we would be positioned to complete the destruction of ISIS in Syria.

We think the strategy outlined here, requiring a modest commitment of U.S. ground forces, would have a reasonable chance of defeating ISIS in both Iraq and Syria. But an even more aggressive commitment of U.S. ground forces would provide greater assurance. The current administration will be hard pressed to accept even the modest commitment of ground combat forces we've suggested, much less a major commitment on the scale needed to assure victory. But this will be a long war and a new administration will assume office in 14 months.

Option 3 - Complete Relaxation of Political Constraints

The challenge facing any proposal that requires a major commitment of U.S. ground forces is the hangover that has inflicted the American psyche from our struggles in Afghanistan and Iraq. All but forgotten is our experience during the first Gulf War, when we deployed a very large force which achieved the goals set for it and returned home to grand parades, all in a year's time. The strategy proposed here will draw on that experience while avoiding the errors that have caused so much pain in the more recent conflicts.

As with the strategy outlined above, there will be three major lines of effort; diplomatic, information and military. The first phase will involve a major diplomatic push to gain firm commitments from our friends in the region. They will be required, with our assistance of course, to create a force capable of governing the areas from which we expel ISIS in both Iraq and Syria. That is a major task involving police to maintain civil order, civil engineers to restore utilities, sanitation workers to pick up trash and the myriad other functions of government. Only when clear progress toward building such a force is evident will we begin to deploy ground forces to the region, at which time an information offensive designed to discredit ISIS in the eyes of those living under their yoke will begin. Support to those already fighting ISIS, both Kurds and Sunni Arabs, would continue unabated as this process unfolded. Our diplomats will also be tasked to resolve the future of Bashar al-Assad and his regime before the attack on ISIS in Syria begins.

Absent arbitrary constraints on the size of the force to be deployed, our military leaders will likely embrace the dictum advocated by General Colin Powell and adopted by President George H. W. Bush in the first Gulf War. They will confront ISIS with overwhelming force, probably totaling more than 100,00 soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines. The U.S. force in the first Gulf War totaled more than 500,000 and was augmented by substantial ground forces from the United Kingdom, France, Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Given the global nature of the threat posed by ISIS and the Islamic Jihad they purport to lead, there should be no shortage of nations willing to join the cause once we make our intentions clear. Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Jordan are prime candidates to contribute both combat forces and the governance force that will fill the vacuum when ISIS is defeated.

Our scheme of maneuver will be dictated to some extent by the degree to which Turkey grants access. Ideally, we would position substantial force in both Turkey and Iraq on their borders with Syria, confronting ISIS with a two front war. Should Turkey refuse, as they did in the first Gulf War, we could mount an amphibious assault from the Mediterranean in the west while the bulk of our force moves on ISIS from the east.

Regardless, the outcome of this contest will not be in doubt. ISIS will be destroyed or driven underground in very short order. As our forces seize urban centers, lines of communication and key terrain, the governance force provided by our regional partners will fall in behind. Their focus will be to maintain order, restore essential services and hunt down any remnants of ISIS that have gone to ground. With the so called Caliphate eliminated, our forces will withdraw to their staging areas and prepare to return home.

But this fight will not be over. ISIS has established a global presence. With the military campaign in Iraq and Syria concluded, our focus will return to the diplomatic and information lines of effort. The United States will take the lead in an international humanitarian effort to relieve the suffering of those who endured ISIS rule and support the return of refugees who fled their oppression. We will spare no effort in bringing to light the abuses that ISIS inflicted on both Muslim and non-Muslim populations. We will counter the ISIS narrative that western crusaders have invaded Muslim lands by flooding the media, mainstream and social, with video clips of our forces departing for home and of our Arab partners governing the areas we have liberated.

Prevailing opinion in the West seems to be that any attempt to defeat ISIS with our ground forces will strengthen ISIS by drawing even more Muslims to their radicalized version of the faith. But our experience in the region does not support that conclusion. The Sunni tribes of western Iraq joined with U.S. forces to drive Al-Qaeda in Iraq from 2006-2008. Those Muslims did not think of our soldiers as crusaders. After Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990 the region's Muslim nations welcomed Western military forces with open arms and fought side-by-side to restore Kuwait's sovereignty.

Our forces departed as quickly as they came and Kuwait's own government in exile, with the help of U.S. Civil Affairs units, filled the vacuum when the Iraqi army fled the kingdom. If we can replicate that model by building an effective governance force prior to assaulting the ISIS strongholds, and withdrawing our forces quickly when the fighting is done, the ISIS narrative will find few receptive ears.

Don't Drink the Kool-Aid

Don't Drink the Kool-Aid

Comments: 0

Comments: 0